He neglect

Neglect is a syndrome with many aspects and uncertain boundaries, of which it is difficult to provide a satisfactory definition. Perhaps the most fitting, to date, remains that of Heiman's 1979: "Unilateral neglect is the inability to address, respond or orient towards new or significant stimuli present in a specific portion of the space, and this inability is not due to sensory or motor defects. " (Heilman. 1979).

Often what is ignored by the Neglect patient is a combination of what is placed on the left with what is placed on the top. In reality this combination depends on the location of the brain damage.

We thank Arianna Cimini for the artistic contribution (It is a designer who interpreted how a patient with neglect would draw a face).

He neglect, in all its many forms, it has a serious epidemiological and socio-demographic impact. Three to five million people worldwide are affected by stroke neglect each year (Corbetta et al. 2005). In many cases, spontaneous recovery occurs, however, this does not eliminate all the symptoms of neglect. However, in about one third of patients the neglect takes a chronic form and this it interferes with the rehabilitation of all other deficits.

The most used tools for the detection of neglect are the pencil and paper tests, because they are easy to use and allow for a’ immediate quantitative evaluation: deletion of lines, stars, letters, copying images, bisection of lines, drawing by heart.

Among the paper and pencil tests, i copying and drawing tests. The patient is asked to copy a drawing or to draw something from memory.

Heterogeneity and complexity in the Neglect

Neglect can be classified according to sectors of space who are involved and to modality in which it manifests itself.

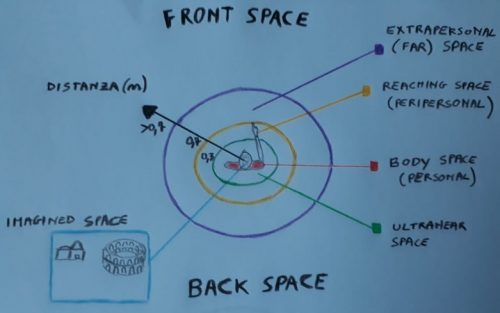

Kerkhoff (2001) distinguishes the different sectors that can be variously affected by neglect:

- body space or personal space, for which in my opinion, more than personal space, one should speak of the body scheme, because one's body is not something like a sector of space;

- l’ultra-near space, at a distance of a few centimeters from the body (Kerkoff says I come in 30 cm, but in reality the distance varies with the different parts of the body) which is perceived as an offshoot of personal space;

- the reaching space (peripersonal), which extends up to approx 70 cm.; but here too it must be noted that the extent of the peripersonal space can vary a lot, for example in the case in which the subject makes use of a tool that allows him to reach more distant objects (Berti and Frassinetti, 2000);

- l’additional staff space (far space).

- the representational space (imagined space): in imagining a scene, the patient can ignore what is placed on the left side (Bisiach e Luzzatti, 1978).

Neglect can affect each of these spatial sectors in a correlated or disjoint form.

As we have already anticipated, neglect can also be investigated according to the modality; we can distinguish a sensory neglect, representational and motor.

In the context of sensory neglect the most typical form is the visual neglect. In fact, in humans and, more generally, in primates, sight is by far the most important sense.

However, neglect can also manifest itself in other sensory modalities. In neglect uditivo the patient does not respond to sounds and speech coming from the left side; when there are several interlocutors, he responds preferentially to those who place themselves in the ipsilesional space regardless of who has spoken (From Renzi et al., 1989).

The sense of smell can also be subject to neglect, although the deficit is difficult to detect , considering the proximity of the two nostrils (Bellas et al, 1988). In neglect somatosensoriale the patient ignores the tactile stimulations, also painful, in the contralesional half of the body (Coghill et al, 2001).

My he neglect it can also affect motor function. In this case there is limited use of the contralesional limbs (Laplane e Degos, 1983).

Main rehabilitation methodologies.

- Visual and spatial scanning (VSS). The VSS therapy it is regarded as the highest level of cognitive training. The patient is stimulated to actively and sequentially scan different parts of a simulated visual field, in order to answer specific questions that may involve reading, copying drawings, the description of figures.

- Virtual Environment Training System. It is an approach that makes use of technology to create a virtual reality that stimulates and helps the patient in the activities of daily life, such as crossing the street, producing gods visual cues that stimulate attention towards the neglected hemifield (Kim 2007). This type of training has the ability to reduce the asymmetry between right and left in patients with neglect.

- Vibration of the neck muscles (NMV). We have the feeling that our head looks perfectly forward if the proprioceptive signals coming from the muscles of our neck tell us that the right and left muscles are stretched equally.. The vibration applied to the muscles of the left side of the neck induces an illusory sensation of stretching of these muscles, evoking the impression that the head is rotated to the right but also that the trunk is rotated to the left. This neutralizes the bias (the error) of orientation towards the right with consequent reduction of the symptoms of neglect (Karnath et al., 1993; Karnath, 1995; Karnath et al., 1996). These effects are transient but one wonders if the repeated application of the vibrations over time can determine the long-term permanence of its effects over time. (G. Kerkhoff, T. Schenk 2012; 1074).

- Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT). It is a "cognitive therapy that implies the conscious protection of the" healthy "side in order to treat the affected side by inducing him to respond in ways that are closer to normal from time to time" (Punt e Riddoch 2006).

- Bilateral Movement Training (BMT). The BMT pushes the patient to use the healthy side as a guide for the affected side (Cauraugh 2010) favoring the performance and development of activities that require the cooperation of the two emilates and that involve coordination and postural control.

- Prismatic adaptation (PA). Using a prism, that shifts the visual field 10° to the right, a significant shift to the left of the patient's hand was found when he was asked to indicate the part of the field placed exactly in front of him (Rode et al. (2006). With the use of this therapy, a significant improvement in both visual-spatial deficits was found

____________

Albert, M. L. (1973). A simple test of visual neglect. Neurology.

Beautiful, D. N., Novelly, R. A., Eskenazi, B., & Wasserstein, J. (1988). The nature of unilateral neglect in the olfactory sensory system. Neuropsychologia, 26(1), 45-52.

Cauraugh, J. H., Lodha, N., Ride, S. K., & Summers, J. J. (2010). Bilateral movement training and stroke motor recovery progress: a structured review and meta-analysis. Human movement science, 29(5), 853-870.

Coghill, R. C., Gilron, I., & Iadarola, M. J. (2001). Hemispheric lateralization of somatosensory processing. Journal of Neurophysiology, 85(6), 2602-2612.

Corbetta, M., Kincade, M. J., Lewis, C., Snyder, A. WITH., & Sapir, A. (2005). Neural basis and recovery of spatial attention deficits in spatial neglect. Nature neuroscience, 8(11), 1603-1610.

De Renzi, E., Gentilini, M., & Barbieri, C. (1989). Auditory neglect. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 52(5), 613-617.

Heilman, K. M., Watson, R. T., & Valenstein, E. (1993). Neglect and related disorders. Clinical neuropsychology, 3, 279-336.

Karnath, H.-O. (1995). Transcutaneous electrical stimulation and vibration of neck muscles in neglect. Experimental Brain Research, 105, 321–324.

Karnath, H.-O., Christ, W., & Heart, W. (1993). Decrease of contralateral neglect by neck muscle vibration and spatial orientation of trunk midline. Brain, 116, 383–396.

Karnath, H.-O., Fetter, M., & Dichgans, J. (1996). Ocular exploration of space as a function of neck proprioceptive and vestibular input—Observations in normal subjects and patients with spatial neglect after parietal lesions. Experimental Brain Research, 109, 333–342

Kerkhoff, G. (2001). Spatial hemineglect in humans. Progress in neurobiology,63(1), 1-27.

Kerkhoff, G., & Schenk, T. (2012). Rehabilitation of neglect: an update. Neuropsychologia, 50(6), 1072-1079.

Laplane, D., & Degos, J. D. (1983). Motor neglect. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 46(2)

Pizzamiglio, L., Guariglia, C., Antonucci, G., & Clogs, P. (2006). Development of a rehabilitative program for unilateral neglect. Restorative neurology and neuroscience, 24(4-6), 337-345.

Punt, T. D., & Riddoch, M. J. (2006). Motor neglect: implications for movement and rehabilitation following stroke. Disability and rehabilitation, 28(13-14), 857-864.

Rode, G., Closs, T., Courtois-Jacquin, S., Rossetti, Y., & Pea, L. (2006). Neglect and prism adaptation: a new therapeutic tool for spatial cognition disorders. Restorative neurology and neuroscience, 24(4-6), 347-356.