Note

| ↑1, ↑3 | Ostelo, Raymond WJG. Physiotherapy management of sciatica. Journal of physiotherapy 66.2 2020: 83-88. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jensen, Rick K., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. Bmj 367 2019. |

| ↑4 | Manx, Robert, and Brent Brotzman. Orthopedic rehabilitation. Edra Masson, 2015. |

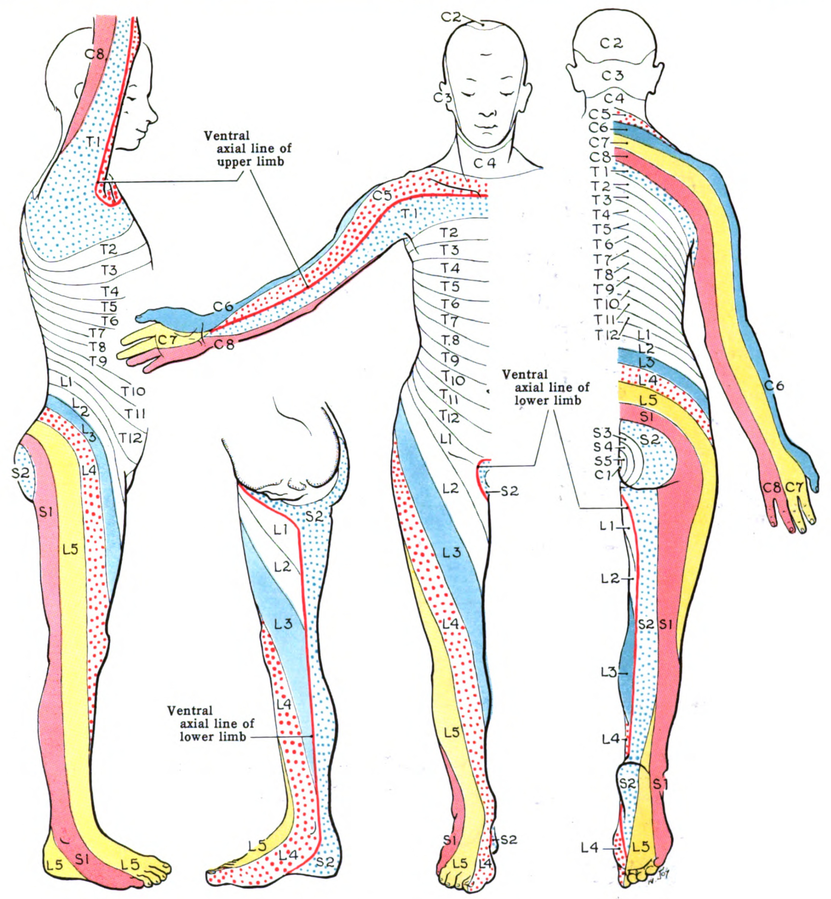

| ↑5 | Hoppenfield S: Orthopaedic Neurology. A diagnostic Guide to Neurologic Levels. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1977 |

| ↑6, ↑16, ↑20, ↑32 | Koes, Bart W., M. W. From Tulder, and Wilco C. Fulani. “Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica.” Bmj 334.7607 2007: 1313-1317. |

| ↑7 | Brotzman, S. Brent, and Robert C. Manx. Clinical orthopaedic rehabilitation e-book. An evidence-based approach-expert consult. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011. |

| ↑8, ↑21 | Jensen, Rick K., et al. “Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica.” Bmj 367 2019. |

| ↑9, ↑14 | Cook, Chad E., et al. “Risk factors for first time incidence sciatica: a systematic review.” Physiotherapy Research International 19.2 2014: 65-78. |

| ↑10, ↑15 | Miranda, Helena, et al. “Individual factors, occupational loading, and physical exercise as predictors of sciatic pain.” Spine 27.10 2002: 1102-1108. |

| ↑11 | Fulani, Wilco C., et al. “Influence of gender and other prognostic factors on outcome of sciatica.” Pain 138.1 2008: 180-191. |

| ↑12 | Plan, Rahman, et al. “Obesity as a risk factor for sciatica: a meta-analysis.” American journal of epidemiology 179.8 2014: 929-937. |

| ↑13 | Schellinger, Dieter, et al. Facet joint disorders and their role in the production of back pain and sciatica. Radiographics 7.5 1987 923-944. |

| ↑17 | Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadski MN, Obucowski N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. Jul 14; 33 2 6973, 1994. |

| ↑18 | Brotzman, S. Brent, and Robert C. Manx. Clinical orthopaedic rehabilitation e-book. An evidence-based approach-expert consult. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011. |

| ↑19 | value, Jean Pierre, et al. “Sciatica.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology 24.2 2010: 241-252. |

| ↑22 | Greenhalgh, S., and James Selfe. “A qualitative investigation of Red Flags for serious spinal pathology.” Physiotherapy 95.3 2009: 223-226. |

| ↑23, ↑25 | Premkumar, A., et al. “Red Flags for Low Back Pain Are Not Always Really Red: A Prospective Evaluation of the Clinical Utility of Commonly Used Screening Questions for Low Back Pain.” The Journal of Bone and Joint surgery. American Volume 100.5 2018: 368-374. |

| ↑24, ↑26, ↑28, ↑29 | Verhagen, Arianne P., et al. “Red flags presented in current low back pain guidelines: a review.” European spine journal 25.9 2016: 2788-2802. |

| ↑27 | Henschke, Nicholas, Christopher G. Maher, and Kathryn M. Reef heap. “Screening for malignancy in low back pain patients: a systematic review.” European Spine Journal 16.10 2007: 1673-1679. |

| ↑30 | value, Jean Pierre, et al. “Sciatica.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology 24.2 2010: 241-252. |

| ↑31 | Prevalence: number of cases at a particular instant. Incidence: number of new cases observed in a period of time. |

| ↑33 | Brotzman, S. Brent, and Robert C. Manx. Clinical orthopaedic rehabilitation e-book. An evidence-based approach-expert consult. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011. |

| ↑34 | Brotzman, S. Brent, and Robert C. Manx. Clinical orthopaedic rehabilitation e-book. An evidence-based approach-expert consult. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011. |

| ↑35 | To the RCGP 1996 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain, London, Royal College of General Physicians, 1996. |